Written by Jen Goodwin

SM can present as someone seeming very shy, not answering questions, not engaging in conversation, and not speaking when called upon or addressed. However, SM is not the same as shyness. While shy people can usually offer some kind of response in order to get their needs met, individuals with SM often cannot speak at all in certain situations — even in moments of severe injury when they urgently need help. Despite society frequently associating situational mutism with Autistic individuals, most Autistic people do not experience SM. However, the majority of people who experience SM are Autistic.

Situational mutism may present as a person who:

Some people who experience SM are able to force themselves to speak, but with great effort and often at significant cost. Individuals with SM — both children and adults — often describe their experience using terms like “freeze,” “frozen,” or “blocked,” suggesting a sensation of paralysis that renders them physically unable to speak. Read more about the experiences of adults with SM in their own words here.

The first thing to acknowledge is that SM isn’t a conscious choice, but a reaction to anxiety – just as shivering tries to warm your cold body, or sneezing tries to clear your nose. It is generally considered to be a protective avoidance strategy to reduce current distress and prevent additional distress. SM can also be a spoon-saving exercise.

If a student has the capacity to do four things, but is expected to be present, listen, speak, behave appropriately, and learn the lesson being taught, not speaking can be the most straightforward and least problematic option to remove from that list.

By removing the possibility of “getting something wrong”, and no longer inviting input from others, the brain is attempting to effectively press pause on interaction without forcing the person to resort to more extreme measures such as aggression, eloping, meltdown, or complete shutdown. In some ways, SM is like a micro-shutdown. During one episode of situational mutism, my daughter was told, “You’re so shy!” One of her greatest advocates happened to be within earshot, and responded, “She’s not shy. She’s just deciding whether or not you’re worth talking to.” While a rather cheeky response, she wasn’t wrong. My daughter’s situational mutism gave her the space she needed to assess who was a “safe person”, with minimal risk to her own regulation while she figured it out. Sometimes this took minutes, sometimes it took months. Sometimes the conclusion she drew was that a person was too overwhelming, and it was permanent.

Like many aspects of neurodivergences, the presentation of SM can be fluid. A child might be very happy chatting with peers at school one day, and not speak the next.

There is usually a change that leads to this. This could include:

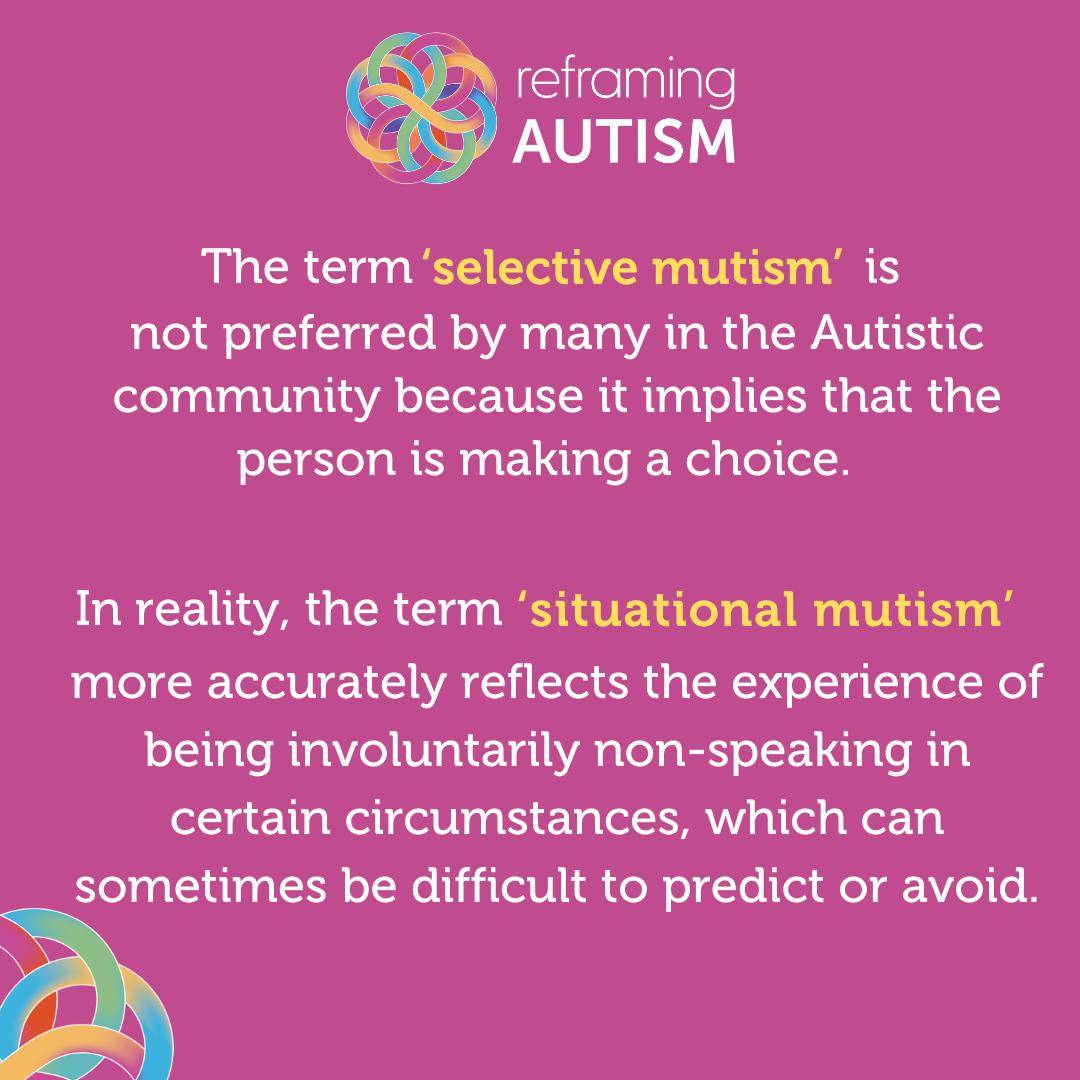

Diagnostically, situational mutism has been classified as ‘selective mutism’ and categorised as an anxiety disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. The official criteria can be described as follows:

‘Selective mutism’ is also the term used by by medical professionals and most teachers. In a neuroaffirming or accommodating environment, as education is intended to be, this definition can be problematic.

A person does not need to be able to speak in the traditional sense to learn, communicate, or socialise; there are plenty of people who are unable, or choose not, to speak for other reasons who are perfectly intelligent, educated, and have friends and a great social life.

Alice Sluckin, President of the Selective Mutism Information and Research Association (SMIRA), suggested 40 years ago, a better term might be ‘Situational Mutism’ (Johnson & Wintgens, 2016). Autistic researcher Damian Milton has helped popularise the term and it is now the preferred term advocated for by those with lived experience of SM as a more appropriate description, as it demonstrates that it is not an active choice by the individual not to speak.

As an ally, you can use use the most neuro-affirming and accurate term – “situational mutism” – and advocate for others to use it too. However, should a person who experiences SM choose to use the term “selective mutism” they are not to be corrected or judged.

Girls are said to experience SM 2 to 3 times more frequently than boys, however there has been speculation that this could be more about societal expectations than natural presentation.

Utilising Christine Miserandino’s Spoon Theory, imagine a boy and a girl in kindergarten both tend to not speak but – as a result of saving the Spoons required for engaging in conversation – are able to sit still in class and focus. The girl is seen as “shy”, “quiet”, and “well-behaved”; she might not even be flagged as experiencing situational mutism, depending on how often it comes into play. A boy would generally not be as well-received if he was quiet and didn’t speak.

Being shy and quiet aren’t seen as positively by society when attributed to boys, and are frequently flagged as a reason for concern or a personality flaw. As a result, from a young age, boys might be more likely to budget their spoons to force themselves to speak, and instead their ability to sit still in class and focus might be in question. But societally, this is more often accepted as “boy behaviour”, the same way that being quiet and shy is acceptable “girl behaviour”.

People who experience SM should not be:

As always, every person is different. Some people who experience SM like it if people acknowledge that they’re not able to speak at that time, others prefer it not to be mentioned. A lack of speech, for some, means a preference to avoid communication; others simply would prefer to change mode. Some people want to be left to work through it themselves, and others would prefer people to recognise it as an expression of anxiety and help them feel regulated and safe.

Don’t make assumptions based on what you’ve been told “people with situational mutism need”, or insist you’re right, based on what another person experiencing SM benefited from. Ask your loved one what their ideal scenario would be if they found themselves unable to speak at work or school.

If the person in question is a child in your class, or a colleague at work, let them know you’d love to be doing the best thing for them.

In the case of a child, engage with their parents and see if you can get some clear preference to act upon; and when utilising these, let the child know you’re trying to do what their parents suggested, and if you don’t get it right it’s okay to communicate this or get their parents to. You might be surprised at how self-aware and self-advocating kids can be if asked!

If it’s an independent adult, advise them that they’re very welcome to share their preferences with you in any way they wish; and if they do, express gratitude, and adopt these preferences as much as possible.

In all cases, let the person experiencing situational mutism know that you understand that their needs and preferences might change, and that you’re always open to changing along with them.

Studies into SM and anxiety have demonstrated such a high correlation that many believe SM to actually be a presentation of anxiety, rather than an independent condition. As such, in order to prevent traumatising an already anxious person, the approach needs to address the core issue rather than their “inability” to speak.

While some medical professionals will address SM with speech therapy, social skills courses, and increased social engagement, this can be seen as forcing anxious people to mask. This puts them at risk of dysregulation and future mental health difficulties in order to prioritise the comfort and convenience of others. It is not “fixing” anything for the person experiencing SM. However, for people with general anxiety disorders, medications, changes in sleep and diet, and seeking out neuro-affirming therapies can be hugely beneficial, so please encourage your loved one to talk to their GP, paediatrician, psychologist, or other preferred medical professional, to get the help needed to address this underlying anxiety – for the benefit of the person experiencing it, not because it’s inconvenient or disconcerting for their teachers or colleagues.

If someone had a health condition that caused them to break bones easily, and they broke their leg, would the approach here be to work on strategies around getting them to walk on their broken leg? Of course not. Would any decent medical professional treat each broken bone, without treating the root health condition? No! So why is this often the approach for Situational Mutism?

What is more important is addressing their anxiety.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5) 5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Johnson, M., & Wintgens, A. (2016). The selective mutism resource manual (2nd ed.). Speechmark Publishing Ltd.

Bethany, S. (n.d.). Selective Mutism and Autism [Video]. Stephanie Bethany. https://www.stephaniebethany.com/blog/selective-mutism-and-autism

Jarrett, C. (2015, July 8). The experiences of adults with “selective mutism”, in their own words. The British Psychological Society. https://www.bps.org.uk/research-digest/experiences-adults-selective-mutism-their-own-words

Keville, S., Zormati, P., Shahid, A., Osborne, C., & Ludlow, A. K. (2023). Parent perspectives of children with selective mutism and co-occurring autism. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 69(8), 1251–1261. https://doi.org/10.1080/20473869.2023.2173835

Zisk, A. H., & Dalton, E. (2019). Augmentative and alternative communication for speaking autistic adults: Overview and recommendations. Autism in Adulthood, 1(2), 103–109. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2018.0007

Jen Goodwin is an AuDHDer in a neurodivergent, neurodiverse family; she lives in the middle of a National Park at the northern edge of Sydney. She runs More Than Quirky – a tailored support service for families with neurodivergent children – from both an academic and lived-experience perspective. Visit More Than Quirky here.

The Reframing Autism team would like to acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the lands on which we have the privilege to learn, work, and grow. Whilst we gather on many different parts of this Country, the RA team walk on the land of the Awabakal, Birpai, Whadjak, and Wiradjuri peoples.

We are committed to honouring the rich culture of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of this Country, and the diversity and learning opportunities with which they provide us. We extend our gratitude and respect to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and to all Elders past and present, for their wisdom, their resilience, and for helping this Country to heal.