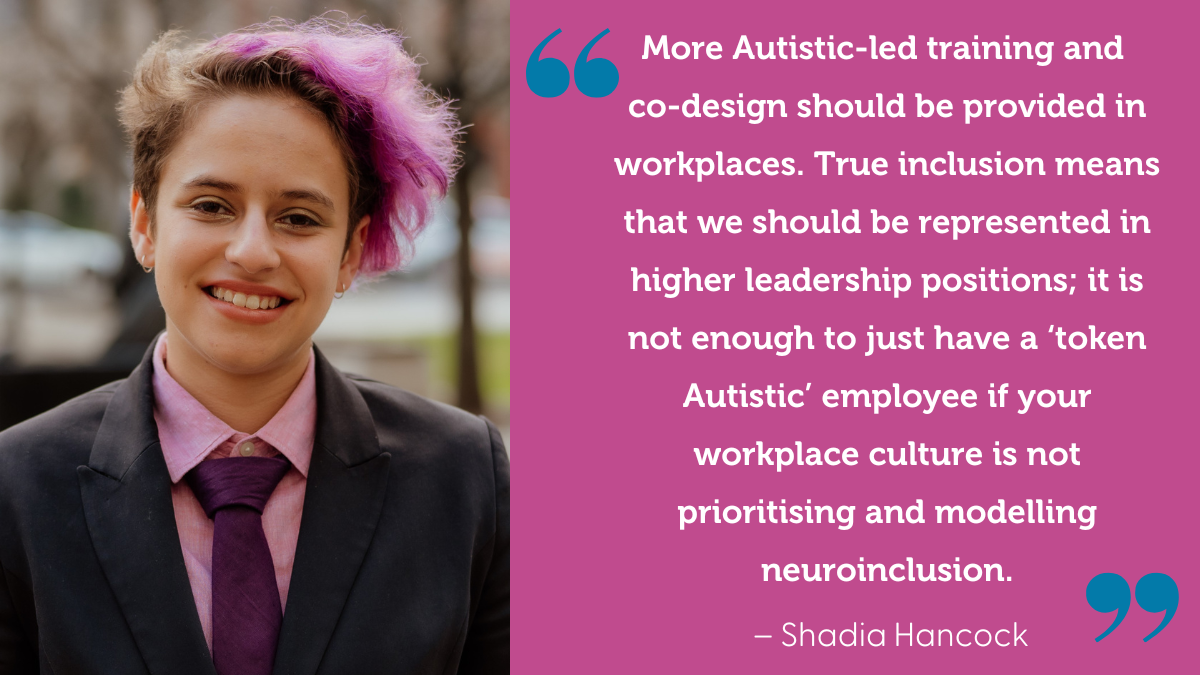

Written by Shadia Hancock

Luckily, my high school provided many opportunities to gain work experience, such as being a waiter or barista at their coffee club, a cleaner, or assisting the IT department. This turned out to be crucial in identifying what professions and settings were meaningful and accessible for my needs. For instance, I was considering studying vet science at university as I have loved animals from a very young age. I decided to undertake work experience at the local veterinary centre, and soon realised that this setting would not be sustainable for me in the long-term. Had I not had exposure to the physical environment, I likely would have pursued a veterinary degree.

As I started to look for work during my later teen years, it became apparent that there were very few employment options that would have been appropriate for my sensory needs, or indeed related to an area of interest. I also worried about being able to juggle school life with employment.

This has provided me with many opportunities to connect with the Autistic community, parents and educators, and organisations. Even better, as Autism advocacy is a SpIn (otherwise known as “special interest”) and deeply important to me, my jobs do not feel like work.

I have had the pleasure of connecting with multiple Autistic entrepreneurs who have also thrived with self-employment. This is interesting given that in Australia, Autistic people are three times more likely than non-Autistic disabled people, and almost six times more likely than able-bodied people to be unemployed (Amaze, n.d.). This is despite many Autistic people seeking work, with employment associated with increased well-being and a sense of purpose (Flower et al., 2021; Jones et al., 2019).

Indeed, Autistic people can exhibit strengths that can greatly benefit the workplace, such as attention to detail, unique problem-solving skills, efficiency, dedication to passions and interests, our ability to hyperfocus, and adherence to routines (LeFevre-Levy et al., 2023). Of the Autistic people who are employed, many are under-employed and in jobs that are below their skillsets (Jones et al., 2019).

While there are more social enterprises specifically recruiting Autistic consultants such as Specialisterne, DXC, and auticon, there are still minimal opportunities available for Autistic adults in Australia (Flower et al., 2021). Moreover, many extant recruitment programs seem to be focused on information technology, administration, and data analysis. This may be due to a common myth that Autistic people are better placed in certain professions such as science, engineering, computing, and technology (LeFevre-Levy et al., 2023).

In reality, our interests and skillsets vary immensely and depend on the individual (Praslova et al., 2023). This may make it difficult for Autistic people in other professions to access employment support services and recruitment programs that offer appropriate opportunities.

To be honest, I have very little interest in mathematics, and wouldn’t know the first thing about coding. I don’t have any remarkable superpowers or abilities. Job opportunities and access for Autistic adults need to be improved across a wide range of careers.

For instance, the job description may be vague, or only focus on the required skills and qualifications (City & Guilds Foundation, 2024). Traditionally, interviews have been conducted in person, with questions being open-ended and asked on the day.

Furthermore, given that employers, colleagues, and job recruitment staff often lack knowledge and understanding of Autistic communication and processing styles, we may be negatively judged on these differences and may not even get past the interview stage (Flower et al., 2021; Jones et al., 2019).

Even when employed, managing our sensory issues and social communication differences may result in communication breakdowns with colleagues and managers.

Many Autistic people decide not to disclose their Autism due to concerns about being stigmatised by colleagues and employers. Given that we can struggle to get past the interview stage, and that many workplaces have limited understanding of Autism, this is not surprising (Jones et al., 2019). However, non-disclosure can also make it difficult to access reasonable and necessary adjustments, which may contribute to burnout.

Additionally, it can be unclear what types of reasonable and necessary adjustments are available or useful (Flower et al., 2021).

Moreover, it can be difficult for Autistic individuals without a formal diagnosis to access reasonable and necessary adjustments (City & Guilds Foundation, 2024; Davies et al., 2022).

This begs the question: Is it better to disclose at the interview stage, or avoid disclosing unless it is absolutely necessary? If the organisation is not understanding or accepting of Autistic employees, how will they respond if we eventually do disclose or request accommodations?

This will benefit all employees regardless of neurotype.

About the Author

Shadia is the proud owner and founder of Autism Actually, and enjoys presenting and consultancy. They are also an ambassador of the Autistic-led organisation, Yellow Ladybugs.

Shadia has completed a Bachelor of Speech Pathology (Honours) degree, and a Cert IV in Animal Behaviour and Training. They have professional interests in Autism, communication access and supports, and animal-assisted services.

Shadia was formally identified with Autism at the age of three and ADHD combined type at 23. Being non-binary, they enjoy discussing the intersectionality of Autism and the LGBTQIA+ community.

As an Autistic ADHDer with experience accessing therapeutic supports, Shadia is passionate about sharing how to view Autism from a neurodiversity-affirming perspective.

References

Amaze. (n.d.). Autism and employment in Australia. Amaze. https://www.amaze.org.au/creating-change/research/employment/

City & Guilds Foundation. (2024). Championing and supporting neurodiversity in the workplace. City & Guilds Foundation. https://cityandguildsfoundation.org/what-we-offer/campaigning/neurodiversity-index/

Davies, J., Heasman, B., Livesey, A., Walker, A., Pellicano, E., & Remington, A. (2022). Autistic adults’ views and experiences of requesting and receiving workplace adjustments in the UK. PloS One, 17(8), e0272420–e0272420. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0272420

Flower, R. L., Richdale, A. L., & Lawson, L. P. (2021). Brief Report: What Happens After School? Exploring Post-school Outcomes for a Group of Autistic and Non-autistic Australian Youth. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(4), 1385–1391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04600-6

Jones, S., Akram, M., Murphy, N., Myers, P., & Vickers, N. (2019, March 28). Autism and Employment. Amaze. https://www.amaze.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Employment-Community-Attitudes-and-Lived-Experiences-Research-Report_FINAL.pdf

LeFevre-Levy, R., Melson-Silimon, A., Harmata, R., Hulett, A. L., & Carter, N. T. (2023). Neurodiversity in the workplace: Considering neuroatypicality as a form of diversity. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 16(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2022.86

Petty, S., Tunstall, L., Richardson, H., & Eccles, N. (2023). Workplace Adjustments for Autistic Employees: What is ‘Reasonable’? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 53(1), 236–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-05413-x

Praslova, L., Bernard, L., Fox, S., & Legatt, A. (2023). Don’t tell me what to do: Neurodiversity inclusion beyond the occupational typecasting. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 16(1), 66–69. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2022.105

Romualdez, A. M., Heasman, B., Walker, Z., Davies, J., & Remington, A. (2021). “People Might Understand Me Better”: Diagnostic Disclosure Experiences of Autistic Individuals in the Workplace. Autism in Adulthood, 3(2), 157–167. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2020.0063

The Reframing Autism team would like to acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the lands on which we have the privilege to learn, work, and grow. Whilst we gather on many different parts of this Country, the RA team walk on the land of the Awabakal, Birpai, Whadjak, and Wiradjuri peoples.

We are committed to honouring the rich culture of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of this Country, and the diversity and learning opportunities with which they provide us. We extend our gratitude and respect to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and to all Elders past and present, for their wisdom, their resilience, and for helping this Country to heal.