Written by Dr Sarah @autisticdoc

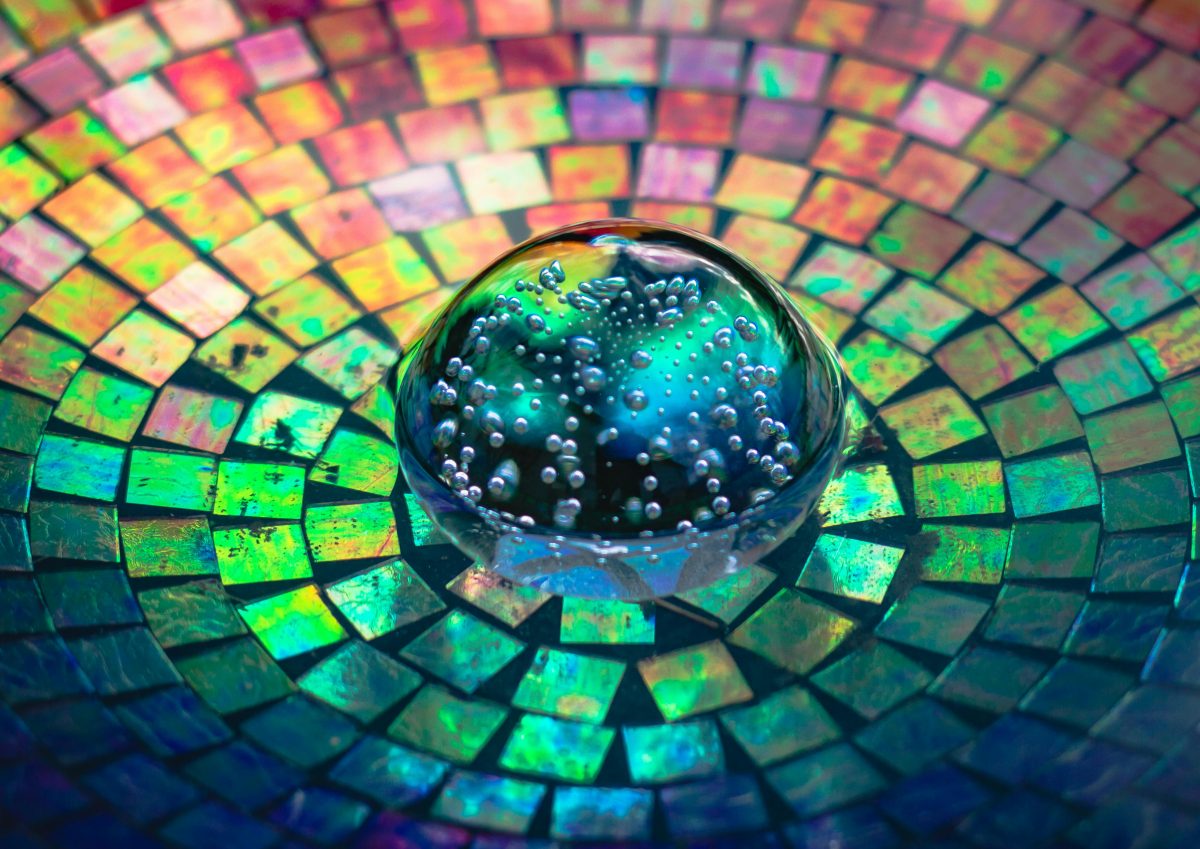

Paul Simons’ “Graceland” conjures galloping horses. Spiky pink zigzags zoom across a black backdrop to “The Hall of the Mountain King”. Slow orange waves rise like an enormous tide with Ravel’s “Bolero”. Each song always evokes the same image. Sometimes, although fortunately not often, the images that appear with music can be quite scary. Lou Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side” is accompanied by an axe murderer, ominously stalking through a desert with blood dripping from him. (Unfortunately, the chords from this song are used in a lot of media, so the scary axe murderer may appear unexpectedly, filling me with dread.)

Occasionally, too, I’ll get a sort of reverse effect where I see an image associated with the song in my environment, and that makes me “hear” the music in my head.

I also experience time as shapes, a sort of pie-chart that appears when I think what time an appointment is, or how many minutes I have to make the walk from carpark to office. Sometimes, I will make a cognitive error with my time imagery. My images for “quarter past” and “quarter to” the hour are very similar, and I will mix them up, leading to me being either very early or very late!

I used to think that everybody experienced the world this way. It wasn’t until I was identified as Autistic, at the age of 38, that I learned this is a phenomenon special to my Autistic neurology.

It is called synaesthesia and is a sort of crossover of sensory and cognitive pathways, where one cognitive or sensory experience triggers another, different, sensory or cognitive experience.

Not every Autistic person has synaesthesia, but it is far more common in Autistics than it is in non-autistics.

When my son was identified as Autistic at a young age, I went through a process of recognising my own Autistic traits in him. Once I self-identified, I yearned to have something on paper to “prove” to him that I’m Autistic just like him. This led me to seek a formal diagnosis, which has been transformative for me and my Autistic kids. (My daughter was also recently identified.) I realise I’m very privileged to have the financial resources to seek a formal diagnosis, and that women are at high risk of being misdiagnosed, which can make the process impossible. So I definitely think that Autistic self-identification is valid.

I am a geriatrician, which is a specialist for older people – a bit like a paediatrician is a specialist for kids. I diagnose people by their “colour”, and certain diagnoses have become saturated with colour for me.

I work in the Emergency Department of a hospital and, thanks to my Autism, I am a fast and accurate diagnostician. When I see a patient, the results of their blood tests, their X-rays, their symptoms and the things I find when I examine their body fall neatly and beautifully into satisfying patterns. The diagnosis comes like lightning to my mind. I will often blurt out the answer while my neurotypical counterparts plod through their diagnostic reasoning. I wait impatiently while they ponder, eager to get started on treatment.

This confused me as a junior doctor, as I would wonder why it was taking the others so long. Now I know that this strength of mine is an Autistic thing, borne of seeking and finding patterns throughout my life.

Non-autistic doctors might use medical concepts they’ve learned and apply them to individual patients, step by step. I use my memory bank of thousands of sick patients, categorised by diagnosis, to quickly match the pattern in front of me to the correct one.

Neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s Dementia, are my passion.

My patient in front of me is elegantly dressed, her white hair meticulously arranged. She smiles, to cover up her embarrassment that she can’t remember my name or what this appointment is about. She’s not sure what day it is. “Oh, ever since I retired the days all just seem the same to me.” She introduces me to her daughter, whose eyes are tight with concern. My patient announces, “And this is my mother, Lindy”, accidentally substituting a word from within the right category (family member), but not the correct word (daughter). A semantic error, we call this.

Green floods my mind.

Now that the diagnosis is triggered in my brain, I carefully assess my patient and her dementia. I’m focused like a laser on finding out what her disabilities are, what treatments will help, what supports are needed for her and her worried family. There is much to do and no time to waste – I really love my job.

I can only hope my children will also have synaesthesia, because it truly enriches my life. I’m not sure if they will. I sometimes ask them, “What picture do you have in your head?” while music is playing. Sometimes they will have a picture and sometimes not.

However, once when I shared my picture with my son (a diver plunging into the ocean with Underworld’s “Born Slippy”), he gasped in delight, crying, “Mummy, that’s the same picture I have!”. That moment was incredible, as we were linked in this overwhelming shared experience of sound, vision and emotion. As I write this and remember, I’m transported to that experience, as only a person with an Autistic memory can be.

To read more about Dr Sarah’s life as a late diagnosed, Autistic ADHDer doctor and parent please visit her blog, Neurodivergent Doctor.

The Reframing Autism team would like to acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the lands on which we have the privilege to learn, work, and grow. Whilst we gather on many different parts of this Country, the RA team walk on the land of the Awabakal, Birpai, Whadjak, and Wiradjuri peoples.

We are committed to honouring the rich culture of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of this Country, and the diversity and learning opportunities with which they provide us. We extend our gratitude and respect to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and to all Elders past and present, for their wisdom, their resilience, and for helping this Country to heal.